Interviewing Susana de Sousa Dias

Susana de Sousa Dias

Susana de Sousa Dias

by Seray Genç – Yusuf Güven /

My first question is about the increasing popularity of the documentary. Do you agree that there is a boom in documentary and if so for what reason?

Yes and I think there are a range of reasons. Of course, one is the democratization of the cameras and all the editing equipment. They became both much cheaper and easier to handle. So, it is almost natural that we now see a boom in directors and new production companies investing specifically in this genre. And we should also not forget the role of recent European audiovisual policies. Furthermore, documentaries are a powerful tool both for reflecting upon the world, and especially in an image based society, and reflecting upon concepts such as reality, image, and so forth. Furthermore, in conceptual and formal terms, it is a quite open and malleable ground, that can be used not only to explore the potential of the cinematographic and artistic languages but to consider the nature of cinema itself.

You cited the reasons for Portugal but the boom for the documentaries is true for the whole world. Maybe the reason behind is the need for alternative channels for information away from the global actors. Do you think this is a kind of movement against globalization?

I am not sure that we can go so far as to say there is some movement against globalization; occasionally, yes, but the problem is always finding a way of presenting and discussing the works themselves, to circulate them — this is certainly not easy in Portugal. Regarding TV channels, as far as documentary is concerned, they tend to impose specific formats so any novelty or difference in approach is killed off from the start…

For example, in Turkey we have CNN Turk. The same major channels are everywhere they have the same format, the same misinformation. This creates its opposite in a dialectical way. Another reason is of course the drop in the price of equipment makes the situation convenient for filmmakers.

Yes, of course, but I think we must not forget the other side as well: today it is also a bit fashionable to make documentaries.

Is this true also for the feature films?

I don’t think so.

Are you going to do only documentaries or are you planning to make a fiction film?

This is an interesting question because when I started to study cinema I wanted to do fiction films; documentary was a completely distant area to me. It was a kind of out of coincidence that I started making documentaries. In the 90s, I received an invitation to make a documentary on Portuguese cinema between 1930 and 1945, a very relevant period of the dictatorship. It was my first experience with documentaries that used archive material. But it was not until the next documentary that I decided definitely to start making documentaries and to work on archival image in a completely different way to what I had been doing before. Regarding the fiction world, I do not rule it out but for me fiction will be always connected to documentaries. As a matter of fact, I am currently working on a project that lies on the borderline between fiction and documentary.

In all this boom, what are the subjects for documentaries in Portugal? Could you make a classification? We ask this question because we think that your documentary is exceptional.

It is always hard to make classifications because the subjects and the ways of filming them are quite diverse. We have documentaries about contemporary social and anthropological issues, biographical documentaries, especially about artists and writers, historical documentaries, etc, etc… As for the historical, generally the format is very typified: interviews, voice over and archive image used in illustration of the past. They follow a methodology close to the TV formats. On the other hand, we have seen a very strong line of observational documentaries. We have also more personal and experimental works. Although much rarer, they are significant within the Portuguese documentary panorama.

(My) First question about your film; did the idea or the material come first? Did you have the idea at the beginning?

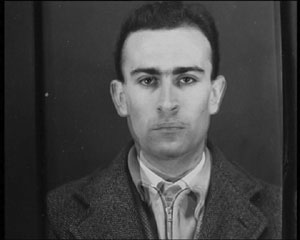

Actually, the material came first. The idea for this documentary, Still Life, appeared the moment I first entered the archive of the political police. After having spent several days on reading files, I discovered quite a few huge albums containing hundreds of photographs of the political prisoners. I was rather impressed by the power of those images but at the same time I was not able to speak about them. I was left speechless. So in a way my film represents the translation of that moment.

The film footage is also from the police archive?

The film footage comes mainly from four sources: the political police, from RTP (the Portuguese state television channel), from ANIM (the National Archive of Moving Images) and the Army archives.

It seems as though discussion about the dictatorship in Portugal is alive at the moment.

Yes you are right. What we are witnessing, as Fernando Rosas, one of the most important Portuguese historians, usually puts it is a struggle for the hegemony of the memory. In other words, a struggle about what will be considered “real history” in the near future. As a matter of fact, there are two major opinions on the April 25th revolution and what it meant for Portuguese history. One camp says that revolution was as an uprising against an authoritarian regime based on oppression, violence and control of people’s mind and therefore positive. The other group – and in my opinion this interpretation is especially now growing stronger and stronger – claims that the revolution interrupted a transitional process towards democratic society. And this group of people correspondingly denies the violent aspect of the 48 years of Portuguese fascism and wants to keep it buried in the past.

And there is another problem. Out of natural causes, the generation of people who actually experienced the dictatorial regime and its real nature will be disappearing sooner rather than later. And this means that the elites in the academic, artistic, social and cultural field will dictate the collective memory of the past and the witnesses who could actually say that these times were different will no longer be alive.

One classic example of what I am trying to say here is the building that used to be the former headquarters of the political police, a very powerful place and symbolic of the regime. This place where many people were tortured, is to be transformed into luxury flats. In other words, this place that serves as an ideal point on which to anchor memory will be erased and made forgotten.

Indeed, this process of erasing our own memory is wrapped up in the subject of our next film.

What was the discussion around the film in Portugal given this situation?

To me it was rather shocking because when the film was shown, the first reaction from the film critics was to dismiss it. They almost denied its existence declaring “this is not a documentary, this is a film without words, this is a film without contextualization, an anachronism”. (As a matter of fact, those were the very fundamental principals of the film!) One film critic even said that the devil should take this film which in Portuguese is really rather an unpleasant expression.

It is a kind of hate.

Yes, the reactions were rather aggressive.

They don’t want to see these images maybe. But how do intellectuals find the film?

Of course we also had positive reactions, some very positive. We had good film reviews; the problem was that they came later.

Another question here is the fact that in Portugal we don’t discuss such things deeply. I mean, there is nothing that could be called a real “public space”. This idea was very well expressed by the Portuguese philosopher José Gil in his book, Portugal Today: the Fear of Existing. When a cultural object (book, film, etc.) enters into the public space it undergoes treatment on multiple layers that in turn transforms it so that by the time the work returns to its author it has already become a new object. It has been thought about, discussed and its meaning has become broader. My film, when it returned to me after some weeks of exhibition, felt like nothing: It was as if I was holding a blind zombie in my arms!

“Whether this is a documentary or not” was not subject to discussion.

I agree. There was never much real discussion about the important issues apart from debates that were organized during the theatrical release.

What were the results of the dictatorship, how many people died, how many suffered?

This is not any mere question of quantification. It is more a question of how the dictatorship still continues to exist in the minds of people. No doubt many political prisoners were brutally tortured and some were killed. And there was a long lasting colonial war, with many dead and left incapacitated, which is still a trauma for many Portuguese. And there were certainly battalions of informers whose identity and exact number will never be known.

There must be some estimates.

No, there are no official numbers apart from the dead from the colonial war. Only recently has the first PhD dissertation on the political police been completed. However, more important than the numbers is the way the regime affected the whole population.

How did that regime end?

Salazar got old and literally fell off his chair. He died from the subsequent brain stroke. He was substituted by Marcelo Caetano. Six years later, Caetano was overthrown by the Carnation Revolution.

Why did you decide to make your film silent? On the other hand the music of the film was very particular.

For me, this is also the result of a reflection on image and history. The question is how history can be shown through documentary. What is usually done in historical documentaries is to build a logical discourse that tends to explain the past. We tend to follow the words and mostly don’t pay real attention to the images. They are just there to carry the narrative and, even worse, the spectator frequently ends up by confusing an image of an event in the past with the actual event.

So, another important aspect of this film was the assumption that an event in the past can never be an objective fact — it is always a fact of memory. The idea of an objective past fact is an epistemological myth. In my perspective, this was one the most important principles to this film. I’m not trying to find a truth in the past and bring this truth into the present. I wanted to make a reflection on the past while also dealing with the memory and with all the knowledge of the present. In this sense, the film is also a reflection on the present.

Regarding the use of archive material, one of my intentions was the questioning of the image itself. My intent was to show images without any pressure from the words, without a speech that commands how we read what we see. Like Didi-Huberman said —the French philosopher whose thesis inspired my work — there is always a dilemma: either you know or you see. The ideal is a dialectic relationship between both. But from the beginning, my option was to move into the field of ‘to see’ so that we didn’t lose the real image. Within this framework of ideas, it was no longer possible to locate the image in terms of time and space and follow a chronology. This is why I left out the words completely.

Did you use the images and footage chronologically?

No, I had a kind of a main chronology: the first years of the dictatorship and its peak, the post-war period, including Portugal joining NATO, the colonial war of the 1960s and then the revolution of April 1974. But the film itself is not chronological and it doesn’t follow any linear narrative sequence – this was another essential element in its construction and the role of the music was essential to building this structure.

I have to say that the editing was the most difficult part of the whole process because editing the material I had gathered was like dealing with a kaleidoscope. Whenever I changed an image in the film, the entire film suddenly became different. And then you start realizing that you can do whatever you want with an image: should you want to, that image can say “a” just as easily as it can say “b”. So, it was difficult to get images interacting in a way that did not subvert their meaning. But the whole point of the editing was to penetrate in and open up the image and not to direct the viewer to read it in any unequivocal way. When looking at Eisenstein’s third image, that strikes the spectator’s spirit through the juxtaposition of the two images, you understand that it is a controlled image. On the other hand, the third image in Godard is not subject to narrative issue or any prior desire of the direct to induce any specific reading on a context specific to the film. Much depends on the spectator, the understanding, their own memories… I think this is a point shared with a certain kind of contemporary films that reflect on the actual nature of the image.

I think also that the dialectics of Godard’s cinema are closer to your film. It is really a creative narration. You are taking the side of your narration. The faces, details, eyes… You created an atmosphere. Another part was the slow motion usage of the footage. You gave time for the audience to think. It completes the idea. Some documentaries claim that they are objective especially documentaries using archives but it always depends on the filmmaker depending on the image is used. For example, I remember the documentary about the Spanish civil war, “El Perro Negro: Stories from the Spanish Civil War”. The director used the archive of a rich man and tries to pull away from the two sides fighting. As a result, he began to support the right wing, the winners of the war. On the other hand I criticize the film because I am taking sides. Your attitude is very different.

Of course I am not indifferent, I take a side. If another director had worked those images it would have been a completely different film. However, one of my principals was never to subvert the image itself. This was one of the greatest difficulties I encountered. Even without using a single word through editing you can construct whatever the discourse, even contradictory, from those images. This is why some of the aesthetical options I took in the film were a consequence of my ethical self-restrictions.