Madaniya: Sudan at the Heart of a People’s Uprising

Seray Genc

Director Mohamed Subahi tells the story of ordinary people yearning for an ordinary life- the beautiful people of Sudan. Whether introducing his film or speaking with us directly, he emphasizes this simple truth. Through characters from different social backgrounds and neighborhoods, characters who represent many aspects of Sudan that are often overlooked or unknown, he invites us to witness a shared dream: the vision of a civil and collective future.

Among them are Esra, a young mural artist; Mumin, a laborer; and Django, a father who joins the protests for the future of his children, making a living as a driver.

Starting in the 2010s, we witnessed global movements seeking freedom, equality, dignity, and representation. Though some managed to topple oppressive regimes, they often encountered eerily similar challenges: state violence, military interventions, rollbacks of hard-won rights, and hopeful beginnings slipping into fragile and uncertain outcomes.

In Tunisia, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali; in Egypt, Hosni Mubarak; and in Sudan, Omar al-Bashir whose 30-year dictatorship fell in December 2018, were each swept away by such waves. Though we focus here on African nations, the spirit of resistance also surfaced elsewhere: from Turkey’s Gezi Park protests (2013) to the U.S.-based Black Lives Matter movement, which began with the Trayvon Martin case and peaked after George Floyd’s murder in 2020. These movements cultivated new cultures of resistance, political consciousness, and civic participation.

With the help of social media which, for all its current controversies, offered more than just headlines and documentary films that archived collective memory, these stories transcended borders. They turned struggle into flesh, bone, and heart and spoke to the conscience of the world.

Sudan, under three decades of dictatorship, banned cinema and many forms of art. Yet, despite this, a legendary generation educated abroad kept Sudanese cinema known through short films, film clubs, underground screenings, and nostalgic returns to the past. Suhaib Gasmelbari’s Talking About Trees captured this very spirit.

The revolution we long hoped for became a reality in December 2018. Mohamed Subahi’s Madaniya takes us beyond that moment. His film explores the period of hope and promise: the sit-ins of April 2019 where people demanded civilian, not military, rule, and the aftermath of the brutal June 3rd crackdown that took the lives of hundreds.

Much has happened since 2019, but the Sudanese people have never abandoned their dreams of a civilian government. The tension between military and civilian powers eventually escalated into civil war in 2023, between the SAF (Sudanese Armed Forces) and RSF (Rapid Support Forces). This forced millions, including the director himself, to flee. Yet the dreams of the people portrayed in Madaniya persist. The film gives flesh and breath to those dreams, bringing Sudan and its people closer to us.

Madaniya, a powerful documentary by Mohamed Subahi, a filmmaker who not only witnessed Sudan’s 2019 revolution, but lived through its hopes and heartbreaks.

At a time when protests were silenced, internet shut down, and lives lost, Mohamed turned to his camera, not as a weapon, but as a witness. Through the voices of Esra, Mumin, and Django, Madaniya reveals the deeply human side of a movement: its art, its labor, its longing.

This is more than a film. It’s a testimony. It’s memory. And perhaps, most importantly, it’s a vision of what Sudan could still become – a country not ruled by generals, but guided by its people.

Muhamed Subahi’s Madaniya was first screened at Sheffield DocFest and will now continue its journey in Istanbul, Saturdox curated by Necati Sonmez.

Mohamed Subahi

How did you become involved in Sudan’s resistance movement, and how did you begin filming the documentary?

I grew up under Bashir’s regime, a harsh and repressive dictatorship that shaped every aspect of life. It’s all I’ve ever known. That’s true for my entire generation and so is the desire for change.

When I saw people in the streets, risking everything for their rights, I felt compelled to grab my camera and document what was happening. That was how it began. I spent three months filming, and when the sit-ins started, I knew I had to be there. That’s where I met the characters who became part of Madaniya.

Though we meet three main characters in the film, we noticed a fourth character, a young woman named Buh whose song is featured in the trailer. Can you tell us more?

Yes, that’s right, Tasabeeh Byha is a young, revolutionary woman full of passion and vision. Her song during the sit-in was not just an ordinary song; it was a patriotic anthem that inspired and united the protesters around a common cause.

In fact, there were more than four people, I originally filmed with six individuals. But in the end, I had to narrow it down. Three characters are a manageable number for a feature-length documentary in terms of narrative focus.

This has clearly been a long journey — not only for Sudan politically but for you, personally, making this film. Would you say you’re not just a filmmaker but also part of the resistance?

Absolutely. I wasn’t just a filmmaker standing behind the camera, I was part of the daily pulse of that moment. I lived through the events in all their detail, and my personal experience intertwined with my generation’s longing for a dignified life and a homeland that deserves us, just as we deserve it. The camera wasn’t merely a tool for documentation, it became my only means of resistance, of endurance, of preserving memory. I was filming with my heart before my eyes. I felt it was my duty, as both a citizen and an artist, to transform that violent moment into something alive, a testimony to what we dreamed of, and to what we lost.

Working on Madaniya wasn’t a creative decision as much as it was an existential necessity. I was there, among the people, sleeping and waking with them at the sit-in. I lived with them through moments of joy, hope, fear, and heartbreak. This film came from the flesh and soul of that experience, not from the imagination of a distant director. So yes, I am part of this resistance, and I will remain so, even if the tools change.

Could you describe your experience filming during those turbulent days? What happened during the sit-in?

I began filming even before the sit-in took shape, moving between neighborhoods, capturing the fear, hope, and bravery in people’s eyes. When the crowds started gathering in front of the military headquarters on April 6, 2019, I knew this was a historic moment that needed to be documented, not from a distance, but from within.

I decided to be there not just as a filmmaker, but as part of the dream. I stayed in the sit-in for 52 days.

We slept on the ground, woke up to chants and songs, shared meals, painted murals, exchanged stories of a new Sudan. There was an extraordinary energy — a mix of creativity, awareness, and collective spirit.

But over time, the tension grew. Then came June 3rd the day of the massacre. That morning, we woke up to a total internet blackout. No calls, no messages, no updates. We were cut off from the world, as if they wanted to erase us from the map.

Then the violence began. We heard about people being targeted, bodies thrown into the Nile, gunshots in the night. I felt that my life and the lives of those around me was in real danger. As much as I wanted to stay, I was forced to leave, to protect myself and to preserve the footage I had because losing it would have meant losing a rare testimony of a moment that may never come again.

Your film doesn’t follow a strict chronological timeline. Events move back and forth — both in time and in the characters’ lives.

The cinematography of Madaniya feels intimate yet politically charged. How did you approach visual storytelling in a time of chaos and danger?

That’s true. Life in Sudan isn’t linear. It’s messy. It moves forward and backward at the same time just like our political history. Sudan has always been caught in a cycle: a popular revolution, a short-lived civilian government, then a military takeover. This vicious circle keeps repeating. That’s why I didn’t want the film to follow a straight timeline, I wanted it to reflect this chaotic rhythm, the emotional back-and-forth, and the unresolved nature of our story. “Madaniya” is my way of breaking that circle, or at least exposing it for what it is.

Women played a visible and powerful role in Sudan’s revolution. How did you reflect this in your film, and what does it mean to you personally?

Women are the beating heart of Sudan’s glorious revolution, and they played a significant and visible role throughout the movement. My film focuses heavily on women and their impactful roles not just through one character like Esra, but through a broader narrative that reflects the strength and presence of Sudanese women in this uprising. Women were not just protesters; they were forces of change, sources of inspiration and resilience in the toughest moments. This film is a tribute to every Sudanese woman who participated and made a difference in the revolution. Personally, I feel a deep pride telling their stories, as they embody the spirit and hope of Sudan’s future.

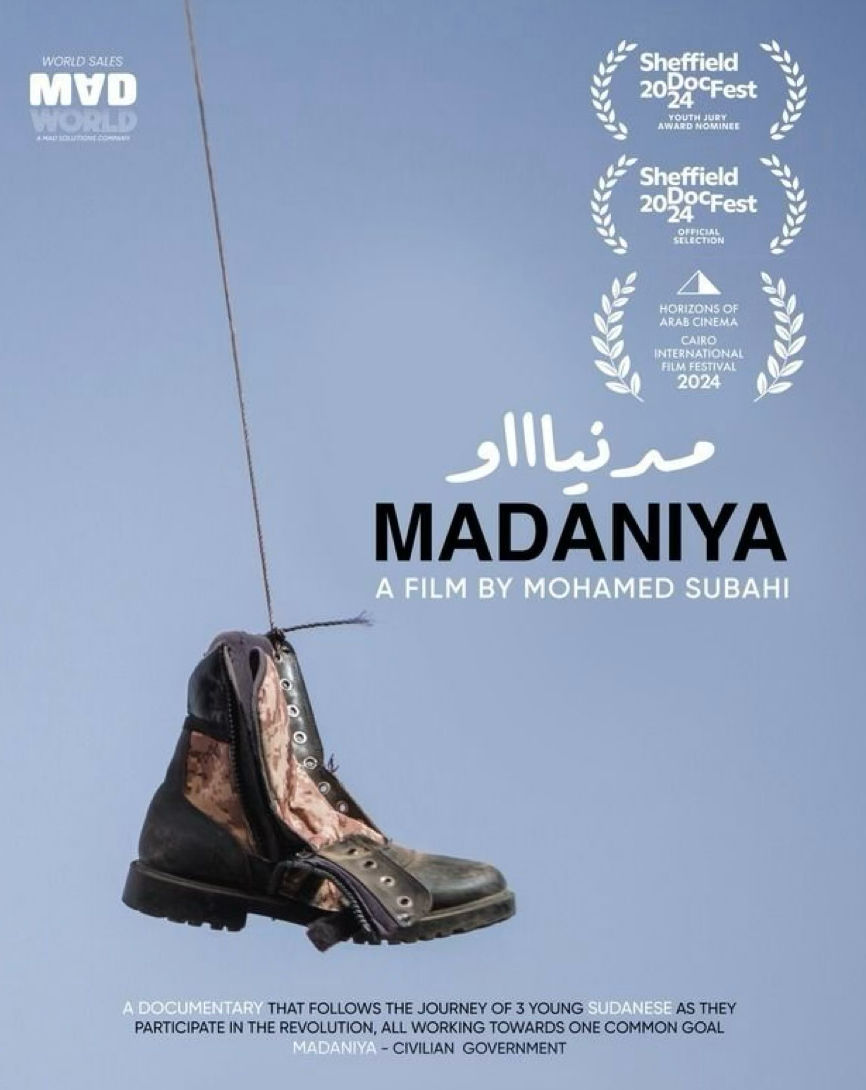

In your poster, we see an army boot — a symbol that strongly resonates with the themes behind the title Madaniya. What does it represent for you, and how did you decide on this image?

The army boot in the “Madaniya” poster symbolizes the oppression and authoritarianism that Sudan endured for decades under military rule. It reflects the deep contradiction between military rule and the civilian governance that the people strive for. This contradiction is at the heart of the film, which portrays the struggle between military repression and the people’s desire for freedom, justice, and dignified life under civilian rule. The boot reminds us of power and brutality, but it also stands for the hope of resistance and building a peaceful, civilian-led future for Sudan.

Even after the fall of al-Bashir, Sudan still faces violence and conflict. You’ve left the country — but do you still maintain ties with Sudan and the people in your film?

Yes, I still maintain strong contact with the people featured in the film. They are still in Sudan, and fortunately, they are doing well despite the ongoing challenges. They continue to serve the community in various ways even after the outbreak of the war in 2023; for example, Mumin works as a volunteer helping provide medical treatment to people in a hospital, and others continue their work actively in Sudan. Our connection remains strong, and I follow their stories and support them as much as I can from afar.

Did you ever connect with Sudanese filmmakers in exile or in Sudan? Do you have a creative or cinema network in Cairo? Is there any solidarity between African or Arab filmmakers?

Yes, definitely. I maintain ongoing connections with many Sudanese filmmakers both inside Sudan and in exile. In Cairo, I’m part of a creative cinema network that supports Sudanese projects and provides a space for artistic exchange and collaboration. There is strong solidarity among filmmakers across Africa and the Arab world; we share experiences and support each other, especially given the challenges we all face in our different environments. This network strengthens opportunities for co-productions and amplifies the voice of independent cinema telling our stories.

Were you able to screen your film in Sudan? If so, how was it received?

Yes, despite the difficult circumstances Sudan is going through, I was able to screen the film inside the country. We held small and discreet screenings in cities that were relatively safe. Even in the midst of war, there are still people who are hungry for stories that reflect their struggle and dreams. However, it’s not without risk today, simply speaking about a civilian state can get you labeled a traitor. That’s the reality we live in. But these screenings, though limited, felt deeply important.

They were acts of resistance, of keeping the conversation alive.

What’s the current state of cinema in Sudan? Could you tell us more about the Sudanese Film Factory, which you’re part of? We’re also curious about the older generation of Sudanese filmmakers — Ibrahim Shaddad, Manar Al-Hilo, Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim, Altayeb Mahdi — many of whom were forced into exile or couldn’t make their films.

Cinema in Sudan is in a very fragile state, especially after the war that broke out in 2023. Many cinemas have shut down or been destroyed, and a large number of filmmakers have been displaced or forced into exile. Despite all of this, Sudanese cinema is still alive kept going by people who believe in its power as a form of resistance and a way to preserve our collective memory.

I was part of the Sudan Film Factory, which played a crucial role in nurturing a new generation of filmmakers. It was there that we learned how to tell our stories honestly and courageously, often with very limited resources. That experience was transformative for me as a filmmaker.

As for the older generation filmmakers like Ibrahim Shaddad, Manar Al-Hilo, Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim, and Altayeb Mahdi they are true pioneers. Despite exile, censorship, and marginalization, they held onto their dreams. They weren’t always able to realize their full visions, but their legacy remains strong. We’re building on what they started. We’re continuing the story, expanding it, and resisting through it.

Documentaries often serve as witnesses to history, helping build consciousness. How do you view the role of documentaries in general?

I firmly believe that documentaries play a vital and significant role in shaping public awareness and deepening understanding of important issues. They are not just a medium to convey information, but a space for reflection, empathy, and resistance. In places like Sudan, where history is often rewritten or erased by those in power, documentaries serve as counter-narratives — preserving voices that might otherwise be silenced or excluded.

For me, making documentaries is not only about recording what happens, but about how we frame those events, how we remember them, understand them, and act upon them. A documentary can transform a political event into a human story — one that transcends borders and lives in collective memory. It is a way of saying: “This happened. This mattered. Do not forget.”

Do you have any future projects planned? Looking back, how has making Madaniya changed you personally — as a filmmaker, as a Sudanese, as someone who had to leave their country?

Yes, I have several projects in mind that I hope to develop soon, focusing on stories that continue to explore Sudanese identity, resilience, and hope.

Making Madaniya changed me deeply — as a filmmaker, it strengthened my commitment to telling honest and urgent stories. As a Sudanese, it connected me even more to my people’s struggles and dreams, despite the distance. And as someone forced to leave my country, it made me realize the importance of memory and testimony, carrying the voices of those still living the reality I captured.

This film is not just my story, but a collective one — and it motivates me to keep creating, resisting, and believing in a better future for Sudan.